Post-Traumatic Stress

Now that we’ve started to understand how the brain functions, and the role that our emotional brain and our thinking brain can have on our experience of traumatic stress, this lesson is going to focus on what happens in our brains after experiencing trauma that causes people to experience things like post-traumatic stress as adults.

Recap — the brain

In the last lesson we explained the triune brain, and how our thinking brain and emotional brain interact to help keep us in balance — the amygdala monitors for danger in the background while our prefrontal cortex keeps us regulated. We also explained how children are more susceptible to experiencing things like small t trauma because their cortex isn’t yet fully developed, which means that when their nervous system detects danger they can become flooded with overwhelming emotions that are beyond their capacity to cope with on their own.

How trauma affects the brain

So why is it, then, that adults can also experience trauma, when they do have a functioning cortex?

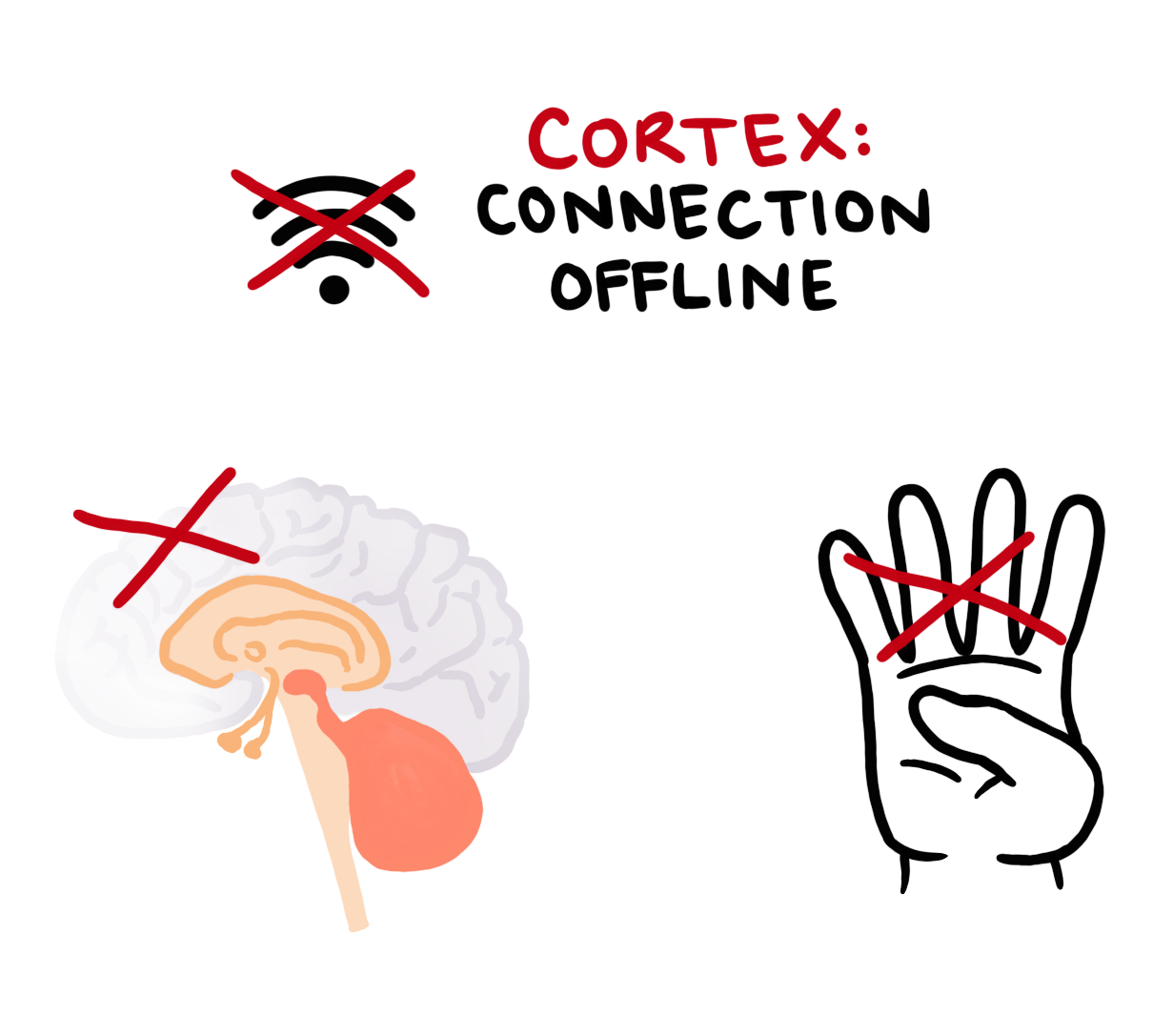

To understand this, it can be helpful to use something known as the ‘hand model of the brain’. If we compare the image of these three parts of the brain with our hand — we can imagine that the base of our palm is the brainstem, our thumb wraps itself into the centre of the hand to make up the limbic system in the middle of the brain, and our fingers wrap over the top to create the neocortex. When our hand stays closed in a fist, this is our fully functioning adult brain.

Now, if as adults we experience a life-threatening event such as one of the big T traumas, as we know our nervous system might have no choice but to go into survival mode down the ladder. When this happens, in order for our survival brain to stay efficient and be able to react quickly without having to think about it, it automatically turns the thinking brain ‘offline’.

What this looks like in our hand model of the brain is that the outer layer which makes up our thinking brain disconnects and “flips its lid”. When we’re in the yellow or red zone in a danger response, our lid has flipped and we no longer have access to things like our prefrontal cortex — we are running solely on the survival impulses from our emotional brain.

Again, this is a good thing. It’s a necessary response to help keep us safe when we’re in the presence of something life-threatening, so we can just instinctively do what we need to survive.

The downside of this response is that without access to the thinking brain, we can become more susceptible to being flooded with overwhelming emotions that are beyond our capacity to cope, just like a child’s brain during an experience of small-t trauma.

How the brain recovers

As I touched on in an earlier lesson, there are two key elements during an experience of trauma that can prevent us from experiencing post-traumatic stress: action and recovery.

If we’re lucky, we will be able to take some sort of action based on our survival responses, whether that’s running away from that grizzly bear, fighting the grizzly bear, or playing dead on the ground until it goes away.

And after the threat has passed, again if we’re lucky, we are able to find a sense of recovery that un-flips our lid and brings us back to the green zone, whether that’s by returning to the safety of home, getting support from a trusted loved one, by making sense of what happened, or by finding some other way to turn that alarm signal off in the amygdala.

I emphasise that these elements to preventing post-traumatic stress can happen if we’re lucky, because sometimes these elements are out of our control, both as children and as adults.

Post-traumatic stress

If we don’t have the resources, capacity or the opportunity to take action when we’re experiencing a big T or a small t trauma — maybe because we freeze or maybe because that choice is taken away from us — a number of things happen in the brain that can then cause us to have post-traumatic stress.

Without loading up on too much more neuroscience, there are regions in the brain that are in charge of integrating our experiences into time and context. The main regions that do this are the prefrontal cortex, the thalamus, and the hippocampus. When we flip our lid, and our emotional brain takes over, access between these regions shut down.

What this means is that during a traumatic stress response, not only do we become flooded with overwhelming feelings from the emotional brain, but the parts of our brain that can help us gain a sense of time and let us know that this will end at some point, are inaccessible to us. This is part of what can make traumatic stress feel too overwhelming to cope with — the feeling that it will never end.

But it’s also a huge part of what causes us to become stuck in post-traumatic stress afterwards. Normally when we experience something in our lives, our brains will file that event away into long-term memory — it becomes something that happened in the past with a beginning, a middle, and an end.

But when we experience trauma, because these time-keeping regions of the brain have shut down, the experience isn’t able to be processed and filed away into our long-term memory. Instead, it’s almost like they get locked in a place within us that’s frozen in time. They become fragmented and placed outside of a sense of context, often becoming stored away as abstract sensory imprints — images, sounds, smells, physical sensations, emotions and even thoughts.

This sense of timelessness can mean that the body continues to get flooded with this constant sensory information that keeps telling the story that the danger is still happening to us. If we remember back to our lesson on the window of tolerance, having a stress response remain chronic or unintegrated is what causes our window to shrink. This is essentially what post-traumatic stress is: chronic nervous system dysregulation.

Go gently

This is what makes trauma so confusing and complicated, because it’s like this never-ending feedback loop where the stress response flips our lid, which prevents us from accessing our brain’s natural ability to self-regulate, and not self-regulating causes our brain to keep us in a stress response, and on and on it goes.

But I don’t want this to scare you, because we can heal. Our brains are wired for healing, they sometimes just need the right ingredients to help get there.

I want this information, once again, to help you bring some kindness to yourself for why you’ve maybe been stuck in the patterns you’ve been stuck in throughout your life. And by gaining an understanding of how our brains function during times of trauma, we can also start to learn what can be done to work with the brain to heal.

Lesson Review

This lesson explained a little bit more about the brain and how the experience of trauma can disconnect us from a sense of time and lead to post-traumatic stress. We’ve just got one more brainy lesson to go that talks about the triggers and symptoms of post-traumatic stress, before we can finally dive into how our brains can heal. If you’ve come this far, thanks for sticking with me.